Yesterday’s job was tackling File::LockDir, finishing up the conversion to a class, and actually putting it under test.

Locking files on NFS

The original version of this library was designed to do locking of a shared directory on an NFS fileserver. This meant that we had to figure out some workarounds for the inherently asynchronous filesystem.

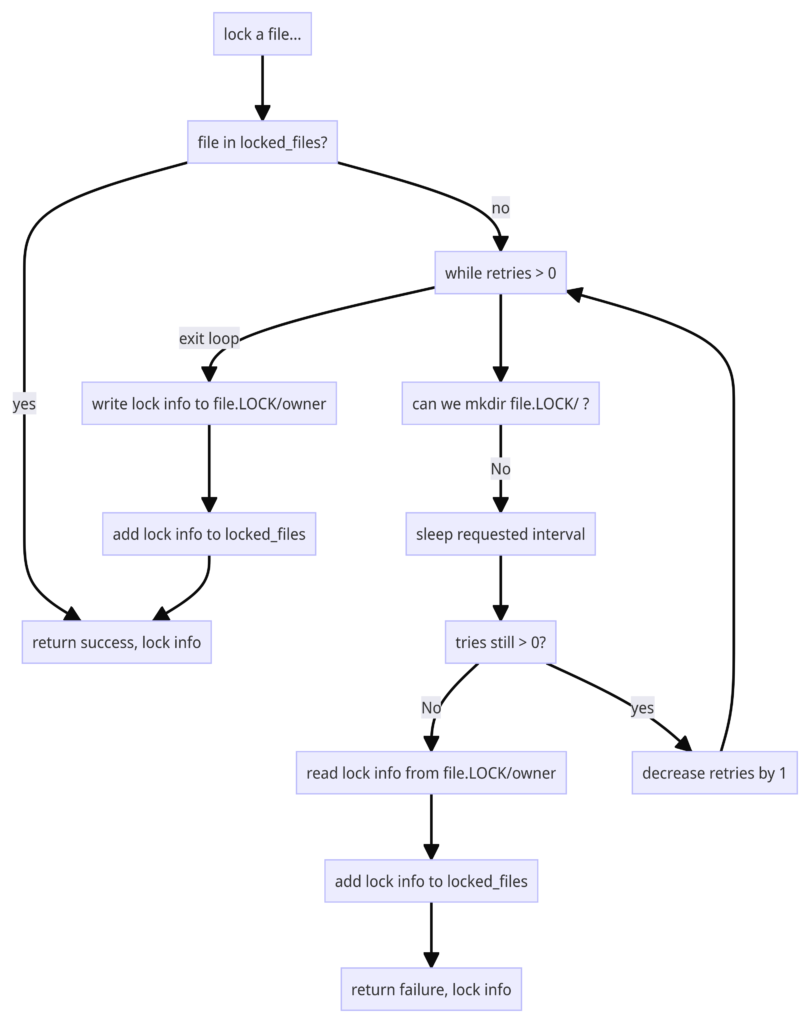

Our big breakthrough was figuring out that mkdir() was atomic on NFS. This meant that we could use the creation and removal of a directory as a semaphore; creating it was atomic, and if it already existed, trying to create it would return an error. Code that needed sequential access to a resource on NFS could make a directory using a standard naming convention. Once it was able to do so, it knew it had locked the corresponding resource. Releasing the lock was a simple matter of removing anything in the directory (we write a file there to record the owner and how long they’ve had it) and then doing rmdir() to release the resource. Anyone trying to get the resource when it was locked could spin on a mkdir and sleep loop until either they timed out or got the lock, which would then be cached in the locked files cache.

Diving in: the very basics

The original version of this code had a package global for the locked file cache, and twiddled the symbol table to add its logger and fatal error callbacks as well, effectively making them package global as well. I wanted to clean all this up, and get everything tested.

First things first: the old library exports the locking functions, and we don’t want to do that anymore. They should only be called as instance methods. Took out the use of Exporter, and got rid of the @ISA and @EXPORT arrays.

Adding tests, the first set of tests is for new().

- We need to test if the logger and fatal parameter validation and installation works. The new test adds throws_ok tests that add an invalid argument for each of those, and a lives_ok one for valid arguments.

- We then also want to test that the valid arguments work, so I passed in closures that pushed data onto arrays in the test’s namespace. Calling these via the File::LockDir methods allowed me to verify that the data was captured for both note() and fatal(), and that fatal() properly did a croak so that we could see where the error had actually occurred.

- Some minor tweaking of the code in File::LockDir was needed to set the values in the object, to add the default note() and fatal() actions, and then the actual code that gets the methods properly in place.

Items of note:

- It was easiest to call the callbacks by assigning them to a scalar, and then calling $callback->(@args). There’s probably a cool way to dereference and call all in one shot, but this works and made it clear what was going on — a better investment of time.

- I forgot several of the getters until I was actually testing the code because the original code had just stored everything in package globals. This was simple and I probably could have left it, but package globals are a code smell, and I wanted to be able to have each File::LockDir object be completely independent. Simpler for testing if nothing else.

- I upgraded testing libraries to Test2::V0 partway through, and it vastly simplified getting the tests written.

The locked file cache

Originally, this was yet another package global hash, which has the advantage of being dead simple to access, but means that all instances of File::LockDir were potentially fighting over the hash. Rather than setting myself up for data races, I decided to move this to the object as well.

The second set of tests actually instantiated the File::LockDir object, and then verified it had properly validated its arguments and saved the data into the object. I chose to implement the method as if it were polymorphic:

- If called with one argument, locked_files() assumed this was a initializer hash and saved the supplied hash reference, after validating that it was as hash reference.

- If it’s not a hashref, then it assumes this must be a key to lookup a locked file and return the lock holder info. It does a hash lookup with the key and returns the value. (Unlocked files will populate the hash with undefs for each lookup; this probably should be insulated a bit with exists() calls to keep from vivifying hash entries that don’t contain anything.

- Last, if there are two arguments, they are assumed to be a key and a value, and this key-value pair is stored in the hash.

How the locking data works, and testing the locking

We start off with a base directory; it doesn’t have to be the same path as the page repository, but nothing stops it from being the same. (In our original deployment, it was easier for us to have the page repository and the locking directory share the same storage; this wasn’t a problem because the filenames of the pages couldn’t contain non-alphabetics that are used to name the lock directory.)

In that directory, we do a mkdir() for filename.LOCK. This is atomic in all the filesystems we care about, and fails if the directory already exists. This gives us an atomic test-and-set operation for the file locking semaphore. Once we’ve obtained the locked directory, no one else is (by convention) going to access it, so it’s now safe to open, write, and close a file inside that semaphore directory. We open filename.LOCK/owner and write the username of the owner plus the date and time.

This requires the following tests:

- Validate that we got a directory name, that the directory exists, and that we can write to it. (If the lock directory can’t be written, we can’t maintain locks.)

- Verify we return success and the lock info if the file is in locked_files. (The cache works.)

- With an empty locked_files, try to lock a file in the lock directory. Verify it succeeds, sets the locked_files cache and that the requestor’s username is in the locking data. (We can lock a file and cache it.)

- With an empty locked_files and a .LOCK directory in the locks directory for the file, verify that we fail when we try to lock the file again, and that we get the stored locking data. (Trying to relock a file that has a .LOCK directory fails, loads the locked_files cache, and returns the current owner.)

- Create an empty directory and cache. Lock a file. Verify it got locked. Fork another process that unlocks the file and exits, while trying to lock the same file with a different user. The unlocking process should succeed, the locking process should succeed, and the file should now be locked by the second user. (The retry process works, and properly relocks the file if another lock owner unlocks it.)

The only really tricky test is the two-process one; that gets handled with Test2::AsyncSubtest, and looks like this:

# 5. Happy-ish path: lock exists, but goes away before tries elapse.

# Locking succeeds.

my $dir = tempdir(CLEANUP => 1);

$path = File::Spec->catfile($dir, 'foo');

# callback capture arrays. Not used this test, but clear them anyway

@l = ();

@f = ();

# Create a new File::LockDir object for this run.

$locker = new_locker(tries => 10, sleep => 1);

# Fork: the child immediately unlocks the file and exits;

# the parent spins waiting for the lock, gets it,

# and waits for the child to exit.

my $ast = Test2::AsyncSubtest->new(name => ‘unlocker');

$ast->run_fork(

sub {

my $locker2 = new_locker();

$locker2->nfunlock($path);

# This is a subtest, so at least one test has to happen.

pass "Async unlock succeeded";

});

# Parent: try to lock.

($status, $owner) = $locker->nflock($path, 0, "RealUser");

is($status, 1, "lock successfully switched");

like($owner, qr/RealUser/, "now locked by RealUser”);

# close out the forked subtest.

$ast->finish;

Other notes and changes

The original spin loop was much more complex than it needed to be. It was trying to calculate if we’d overstayed our welcome on retries with time calculations when a simple countdown was far more straightforward. I added a new method, tries(), and added a tries parameter in new(). The logic now uses the value of the count as the while loop test, causing it to drop out if the count gets to zero. The “should we retry” checks are all “are we out of retries” instead of complicated offsets from the start time of the loop.

Things to do

Things that I might want to do, based on today’s work

Waiting fractional seconds with more iterations might be better. Probably needs some benchmarking to figure out.

The locking data definitely should be changed to something structured to make it easier to generate and consume.